Definite integrals are integrals that have a start and end values which are called the upper and lower limits. There are many applications of definite integrals, including: the computation of the area under a curve, the volume of the solid of revolution, the length of an arc, the surface area of a revolved arc, centroids, first and second moment of area, as well as other physics problems such as work and static pressures.

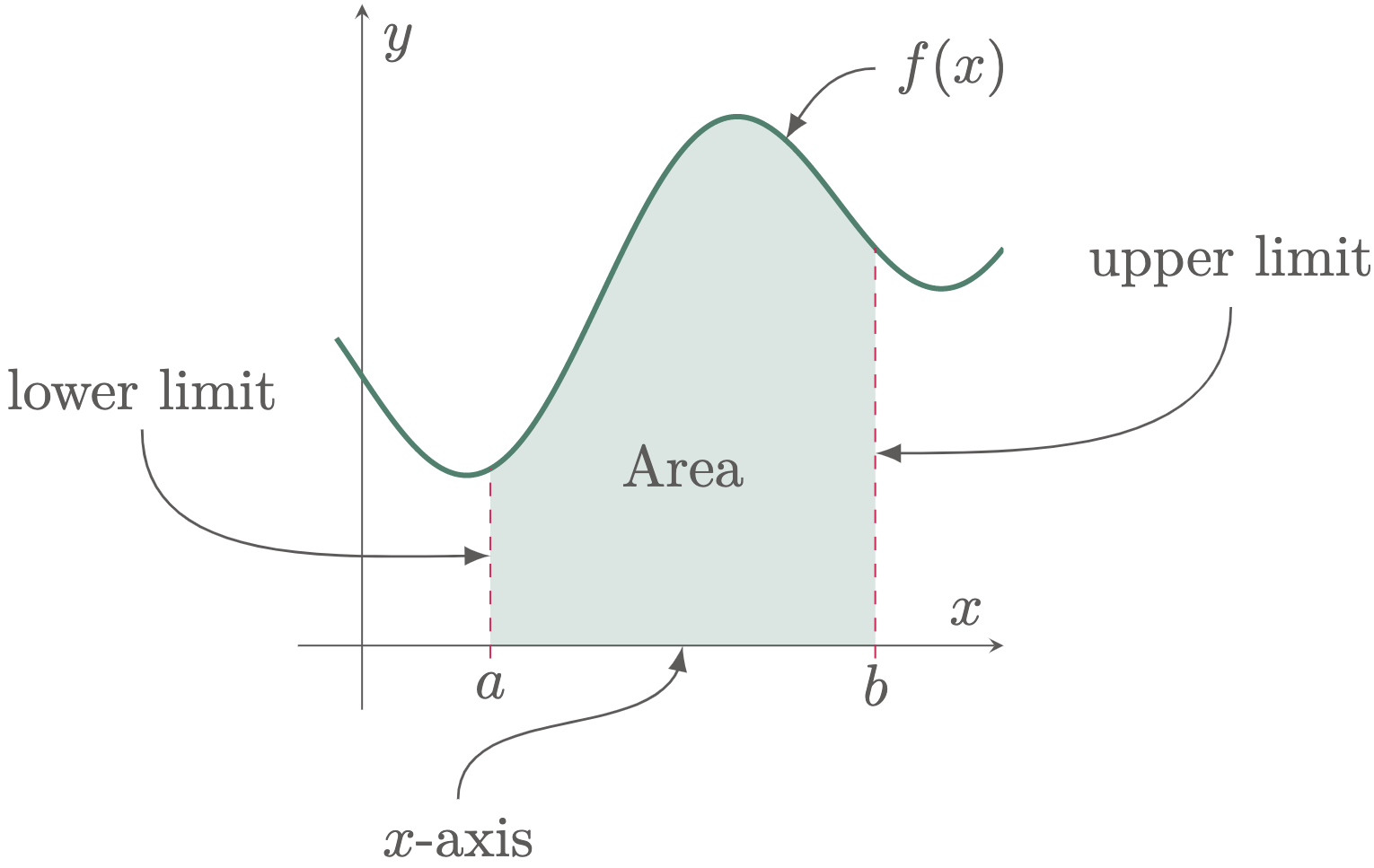

Definite Integrals can be easily understood and visualized using the concept of area under a curve. Consider the figure,

Figure 1: The area under a curve bounded by the upper and lower limits $a$ and $b$ respectively, the $x$-axis, and the curve itself.

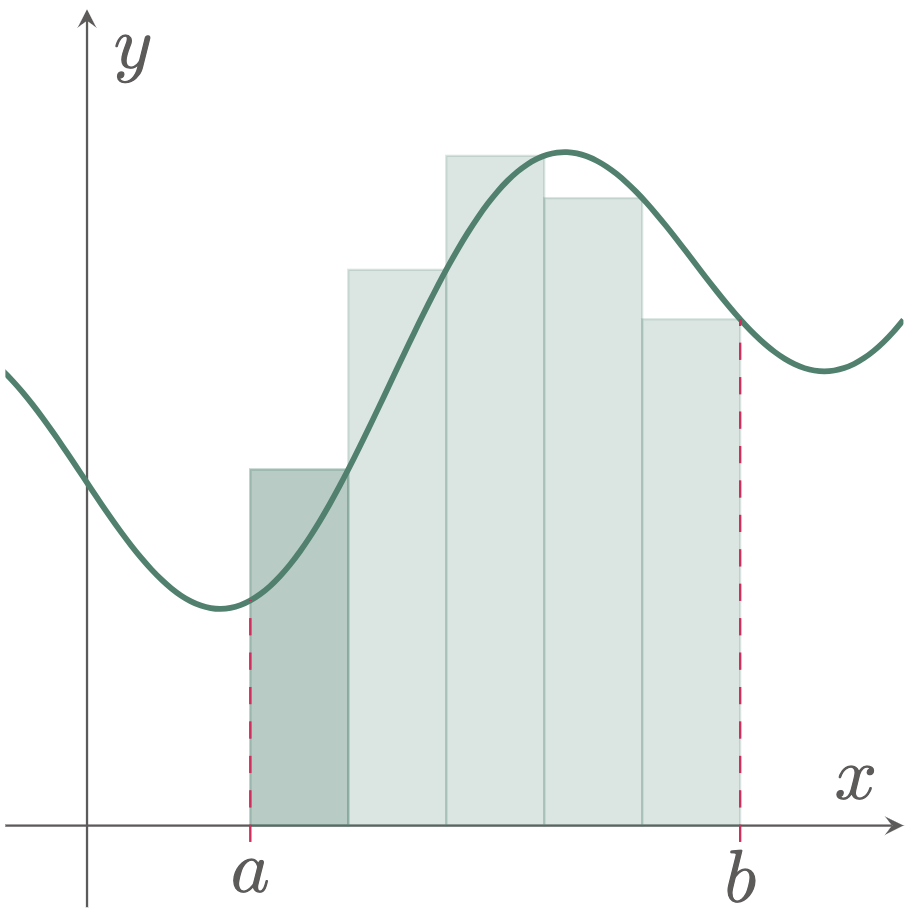

The area bounded under the curve $f(x)$, the $x$-axis, the lower limit $a$, and the upper limit $b$ can be more complex to solve, since the area created has an irregular shape. However, it can be approximated by dividing the area into strips of rectangles ($\fref{1}$), and solving for the sum of the area of those rectangular strips.

Figure 2: Dividing the area into rectangular strips to approximate the area

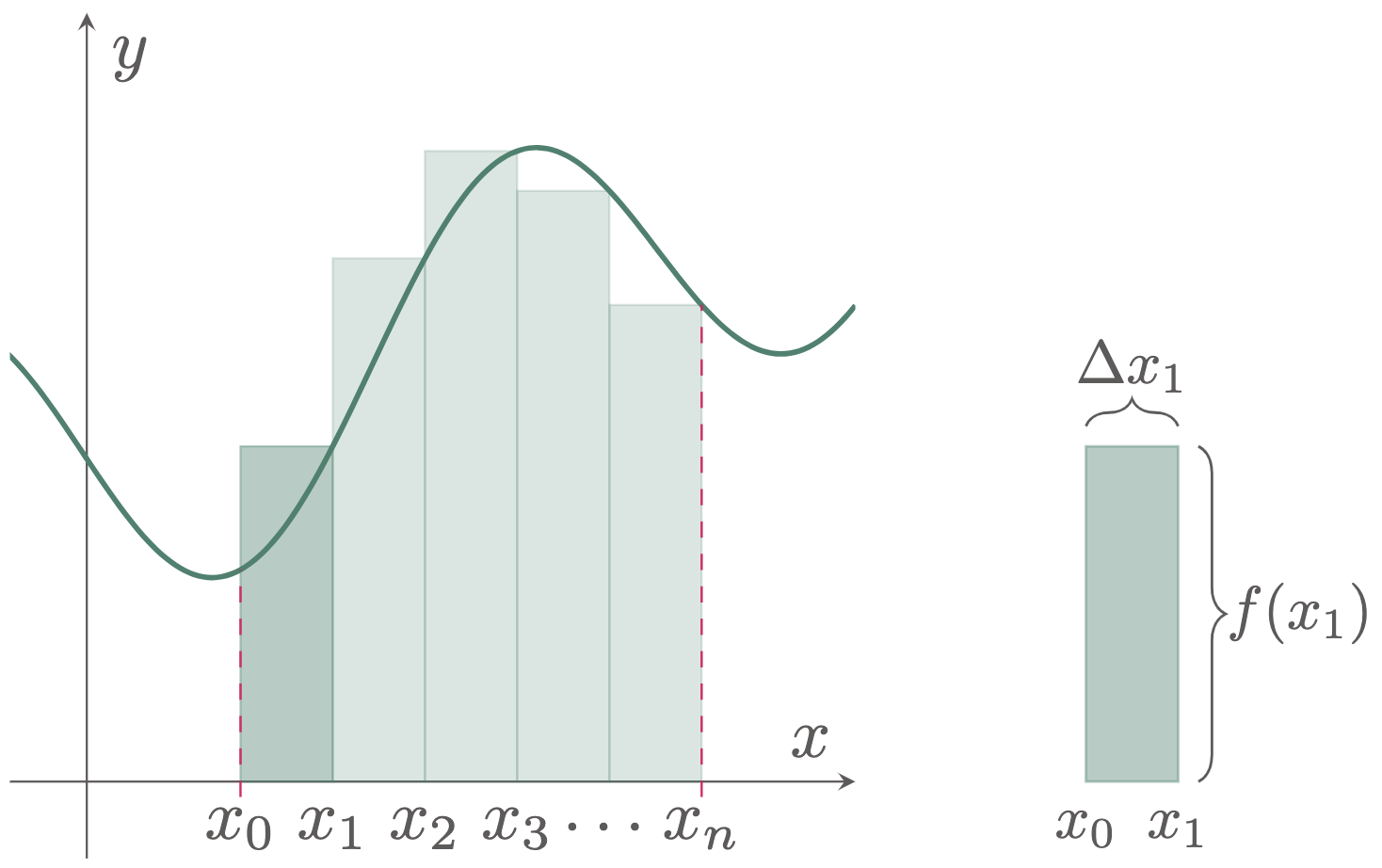

To analyze the steps we need to undergo, we need to isolate the rectangular strips from each other. Moreover, we can substitute the lower limit $a$ with $x_0$ and the upper limit $b$ with $x_n$, where $n$ repesents the number of rectangular strips the area is divided into.

Figure 3: Isolating the first rectangular strip to give emphasis to its parts, $b=\Delta x$ and $h=f(x)$

We can derive the area of one rectangular strip $A_i$,

\[\begin{align*} A &= bh \\ A_i &= [\Delta x_i][f(x_i)] \\ &= f(x_i)\Delta x_i \end{align*}\]Hence, the bounded area is equal to the sum of all the rectangular strips,

\[\begin{align*} A &= f(x_1)\Delta x_1 + f(x_2)\Delta x_2 + f(x_3)\Delta x_3 + \cdots f(x_n)\Delta x_n \\ \end{align*}\]Expressing the function as a Reimann Sum,

\[\begin{align*} A &= \sum_{i=1}^{n} f(x_i)\Delta x_i \end{align*}\]However, we can still improve the equation by increasing the number of the rectangular strips. But as the number of strips $n$ increases, the thickness of each strip $\Delta x$ gets thinner, thus $n$ and $x$ are inversely proportional.

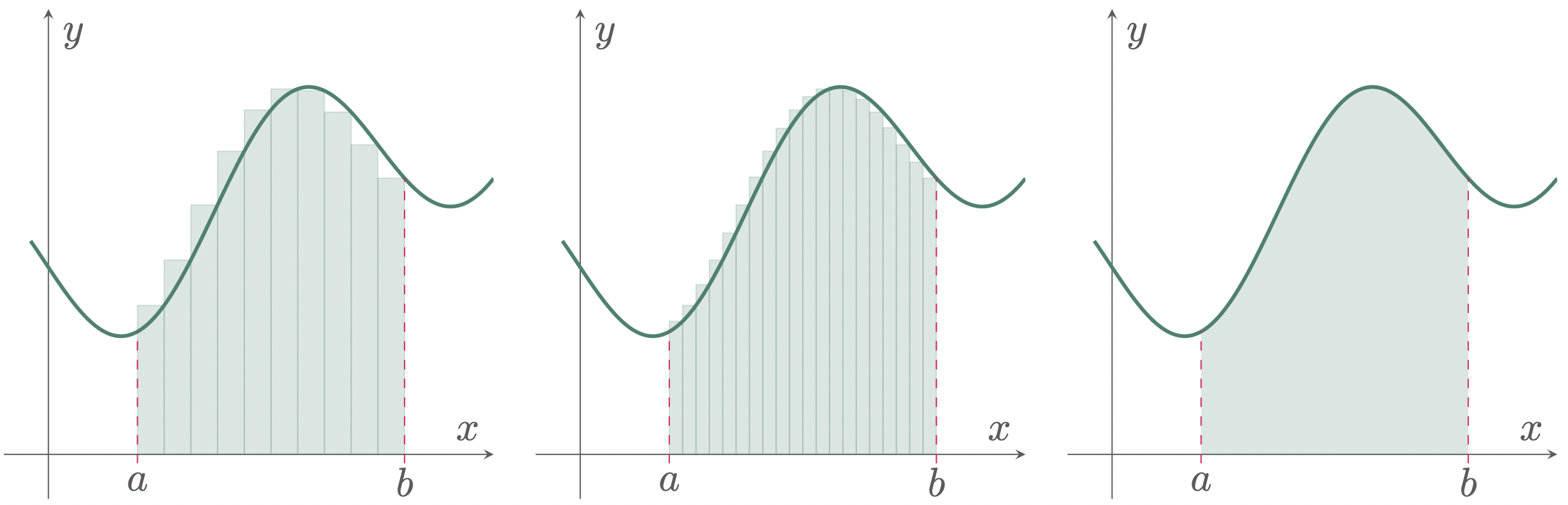

Figure 4: Increasing the number of rectangles infinitely to increase the accuracy of approximation of the area under the curve

If we increase the number of strips to infinity, we can get a relatively good approximation of the area. However, we cannot directly set $n$ to infinity $\infty$, thus, in order for us to evaluate the function, we can approach $n$ to infinity. We have already established that $n$ is inversely proportional to $\Delta x$, hence, as $n$ approaches to infinity, $\Delta x$ approaches 0. Thus, expressing the function as a limit, where $\Delta x$ approaches to 0 gives us,

\[\begin{align*} A &= \lim_{\Delta x \to 0} \sum_{i=1}^{n} f(x_i)\Delta x_i \end{align*}\]This equation can then be further simplified by introducing a the Definite Integral symbol,

$$\begin{align} A = \int_a^b f(x)\,dx \end{align}$$

\(\begin{align*}

\text{Where:}\quad a &= \text{lower limit} & \\

b &= \text{upper limit} \\

f(x) &= \text{integrand} \\

dx &= \text{variable of integration}

\end{align*}\)

Evaluating Definite Integrals

Evaluating definite integrals has similar steps as evaluating an indefinite integral. However, in definite integrals, we no longer need the constant of integration $C$, because we will end up with a specific value since this integral already defines specific boundaries.

Definite Integral is evaluated by integrating first the function, then getting the difference of the integral as a function of the upper limit subtracted by the same integral but as a function of the lower limit.

$$\begin{align} \int_a^b f(x)\,dx &= \Bigl[F(x)\Bigr]_a^b = F(b)-F(a) \label{eq:evaluation of definite integrals} \end{align}$$