$\typB{Sum and Difference of a Definite Integral}$

The integral of the sum or difference of two or more functions is equal to the sum of their integrals.

$$\begin{align} \int_a^b \Bigl[f(x)\pm g(x)\Bigr]\,dx = \int_a^b f(x)\,dx \pm \int_a^b g(x)\,dx \end{align}$$

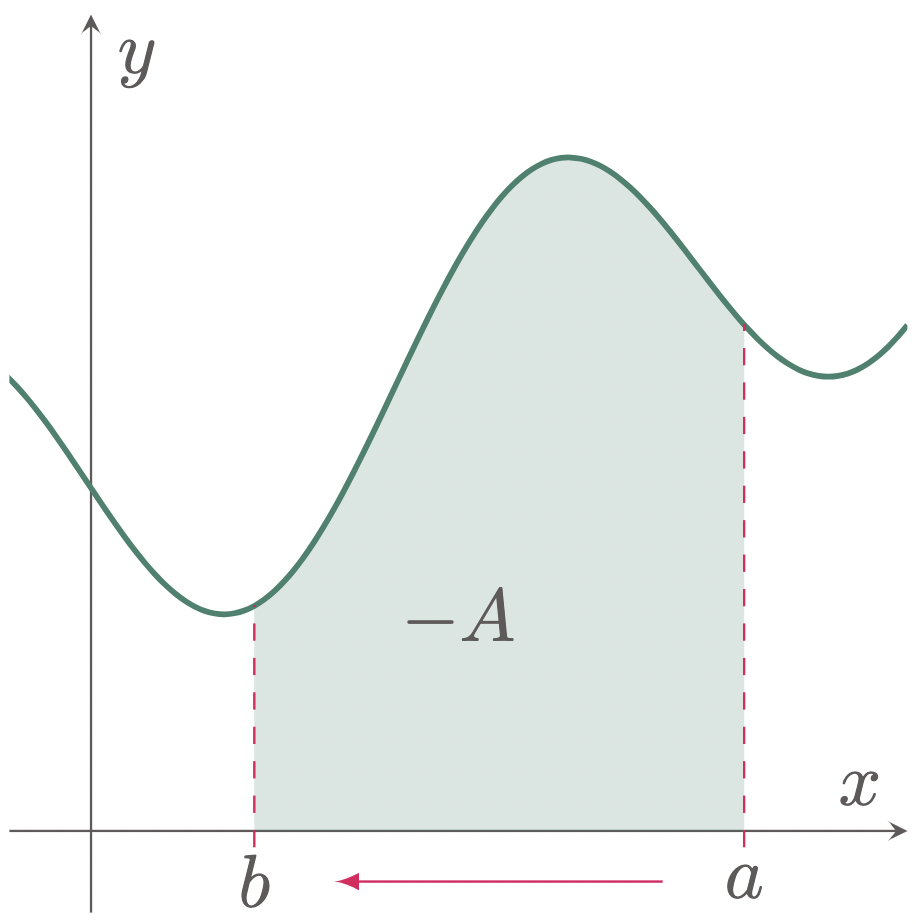

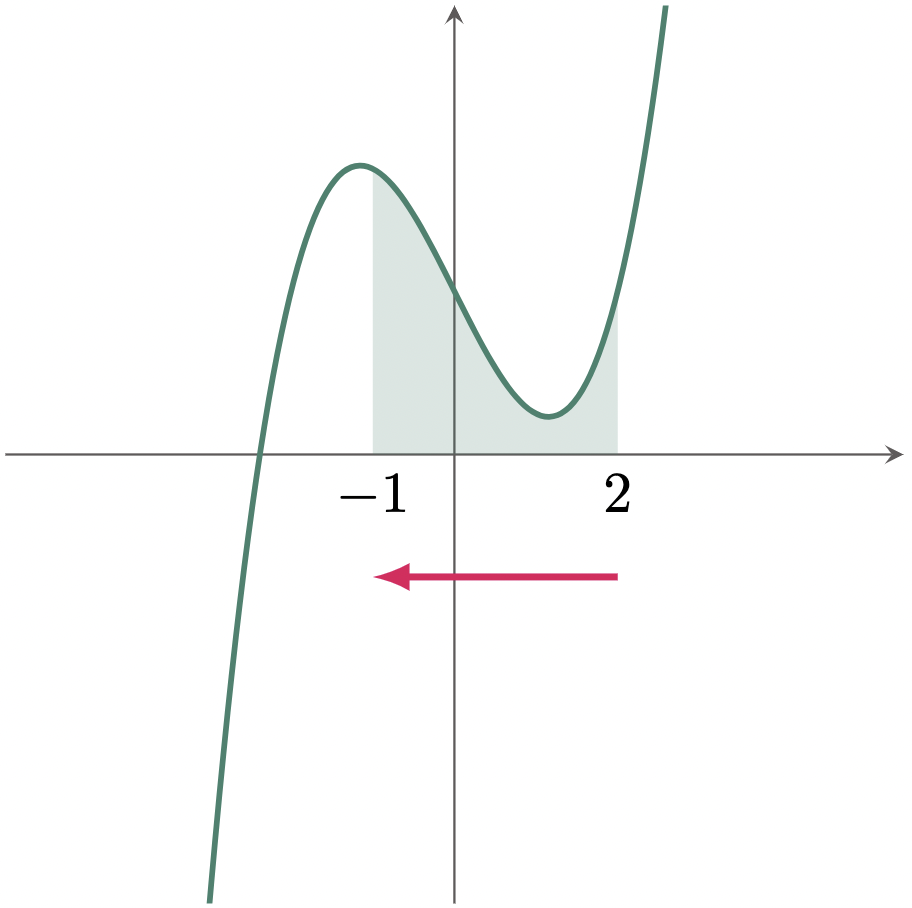

$\typB{Reverse of Limits}$

When the limits of a Definite Integral is reversed, the direction of the interval will also be reversed, thus resulting to the negative of the original integral.

$$\begin{align} \int_a^b f(x)\,dx = -\int_b^a f(x)\,dx \end{align}$$

Figure 1: Reverse of Limits

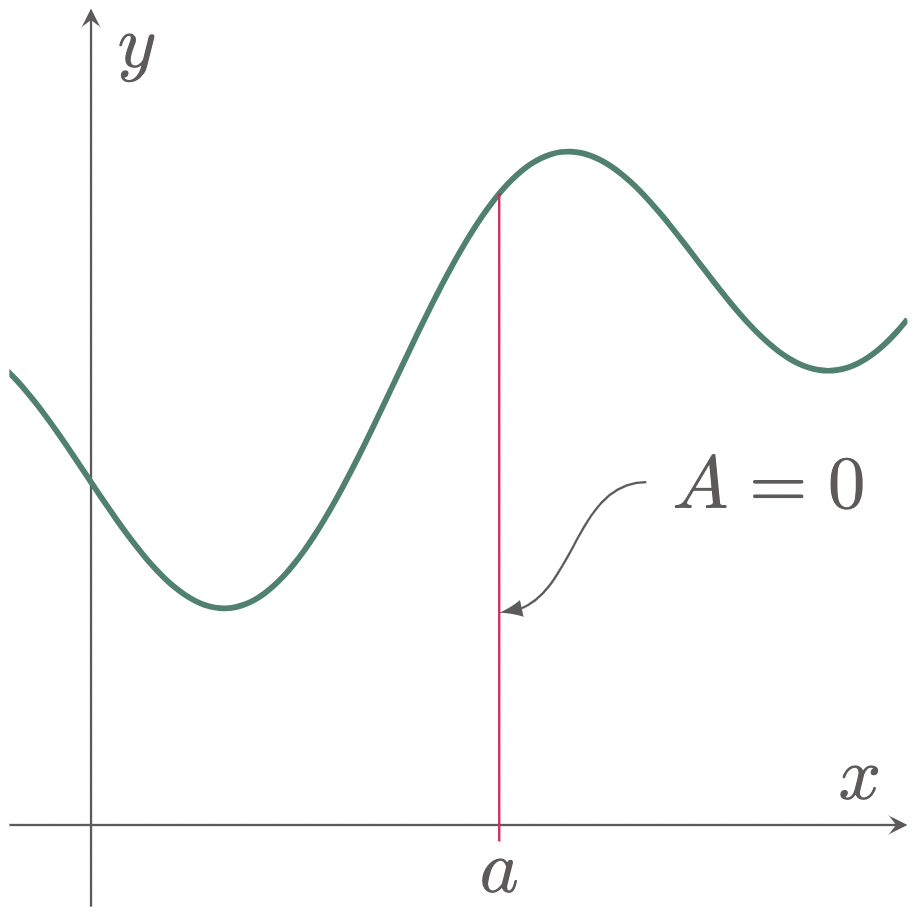

$\typB{Zero Interval}$

In zero interval, the upper and lower limits are equal, hence the definite integral of the function is zero. We can also confirm this by plotting the area (\fref{fig:zero interval results to zero area}).

$$\begin{align} \int_a^a f(x)\,dx = 0 \end{align}$$

Figure 2: Zero interval

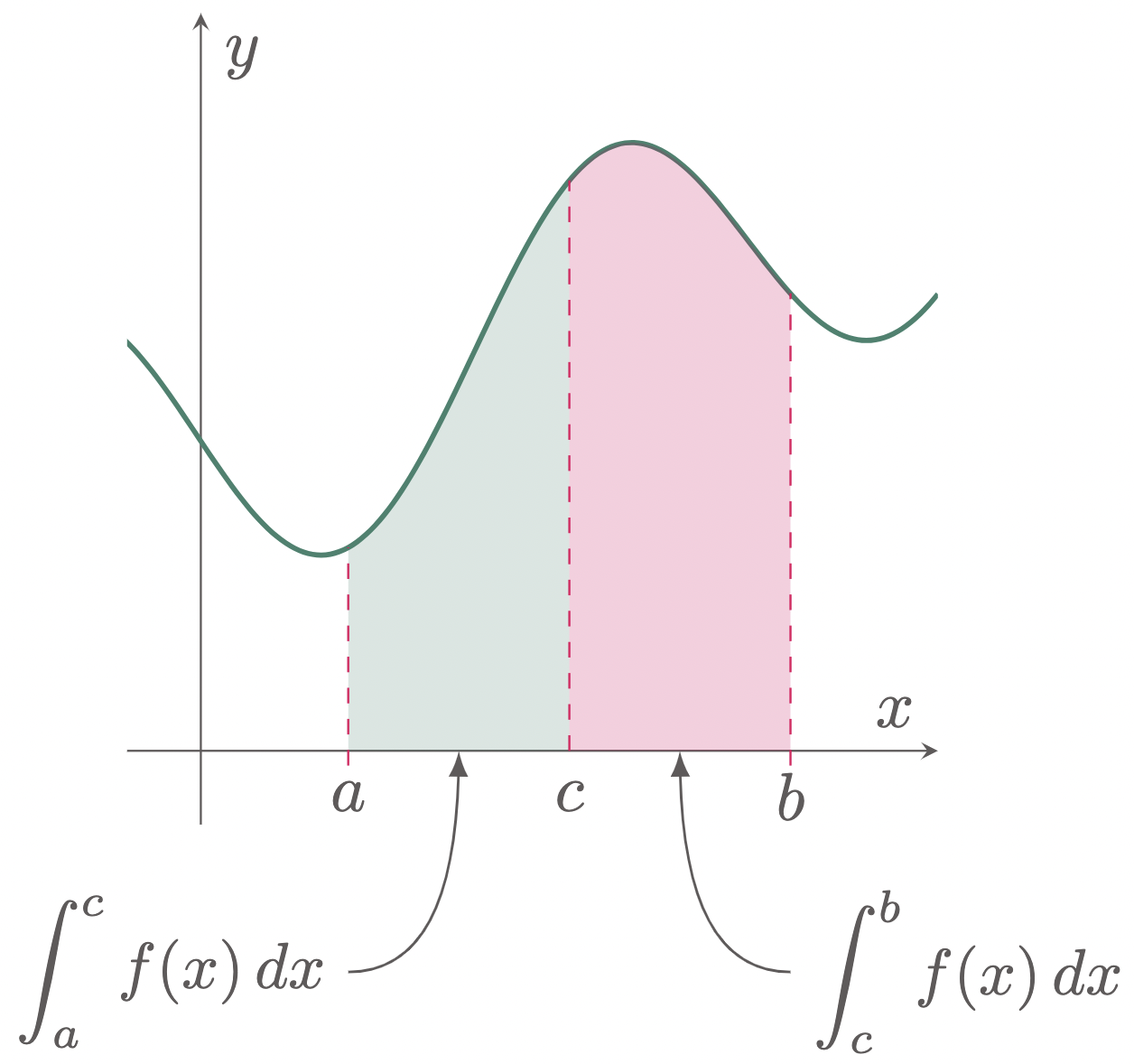

$\typB{Addition of Interval}$

The definite integral of a function at the interval $[a,b]$ can be presented by addition of two definite integrals. Given that $c$ belongs to the

interval $[a,b]$,

the sum of the integrals at the intervals [a,c] and [c,b]

is equal to the integral at interval $[a,b]$.

$$\begin{align} \int_a^b f(x)\,dx = \int_a^c f(x)\,dx + \int_c^b f(x)\,dx \end{align}$$

Figure 3: Addition of interval

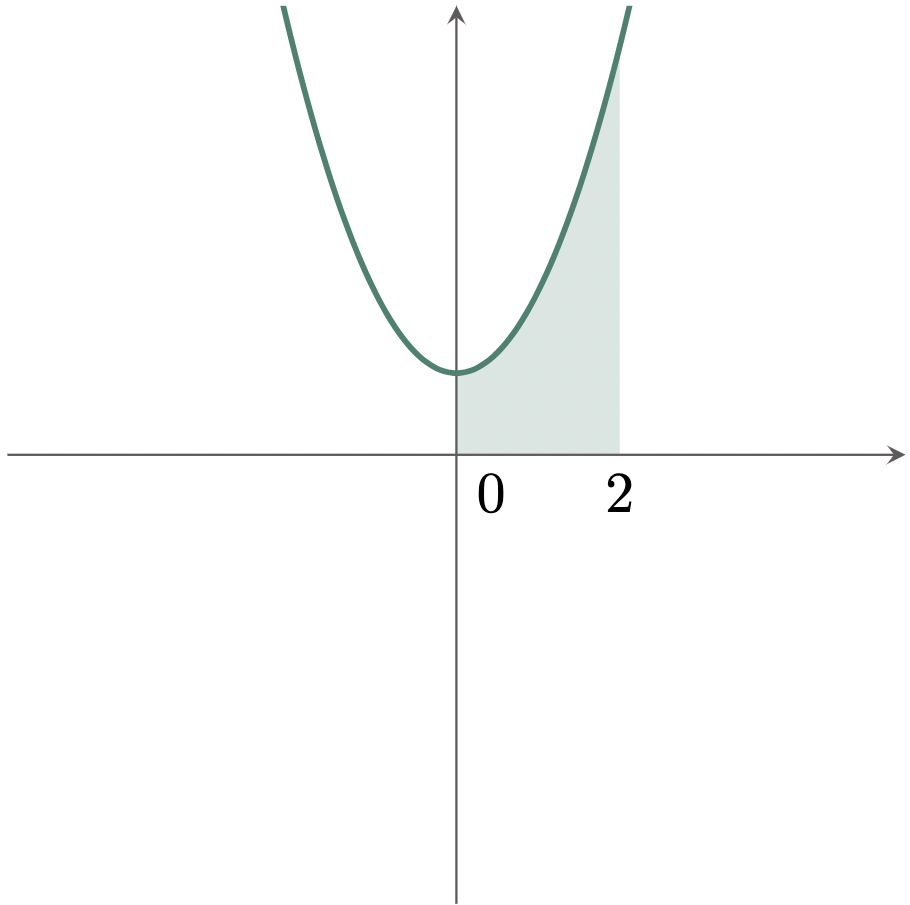

$\example{1}$ Evaluate the definite integral: $\int_0^2 (x^2+1)\,dx$

$\solution$

In evaluating definite integrals, the first step is similar in evaluating indefinite integrals. The only difference is that we can already disregard the arbitrary constant $C$ and indicate the limits after the bracket,

Then to further simplify, $\Bigl[F(x)\Bigr]_a^b = F(b)-F(a)$. Thus,

\[\begin{align*} &= \brk{\frac{(2)^3}{3}+(2)} - \brk{\frac{(0)^3}{3}+(0)} \\ &= \br{\frac{8}{3}+2}-0 \\ &= \frac{14}{3} \tagans \end{align*}\]We can also visualize the definite integral by graphing the function and enclosing it with the upper and lower limits and the $x$-axis.

$\example{2}$ Evaluate the definite integral: $\int_{2}^{-1} \br{\frac{x^3}{2}-2x+2}\,dx$

$\solution$

\[\begin{align*} \int_{2}^{-1} \br{\frac{x^3}{2}-2x+2}\,dx &= \brk{\frac12\cdot\frac{x^4}{4}-2\frac{x^2}{2}+2x}_{-1}^{2} \\ &= \brk{\frac{x^4}{8}-x^2+2x}_{-1}^{2} \\ &= \brk{\frac{(-1)^4}{8}-(-1)^2+2(-1)} - \brk{\frac{(2)^4}{8}-(2)^2+2(2)} \\ &= \br{\frac{1}{8}-1-2}-\br{2-4+4} \\ &= \br{\frac{1-8-16}{8}}-2 \\ &= \br{-\frac{23}{8}}-\frac{16}{8} \\ &= -\frac{39}{8} \tagans \end{align*}\]Though the area is located above the $x$-axis, the order of the limits is reversed. Thus, using the property “Reverse of Limits,” we can prove why the definite integral has a negative value, despite having a positive area.

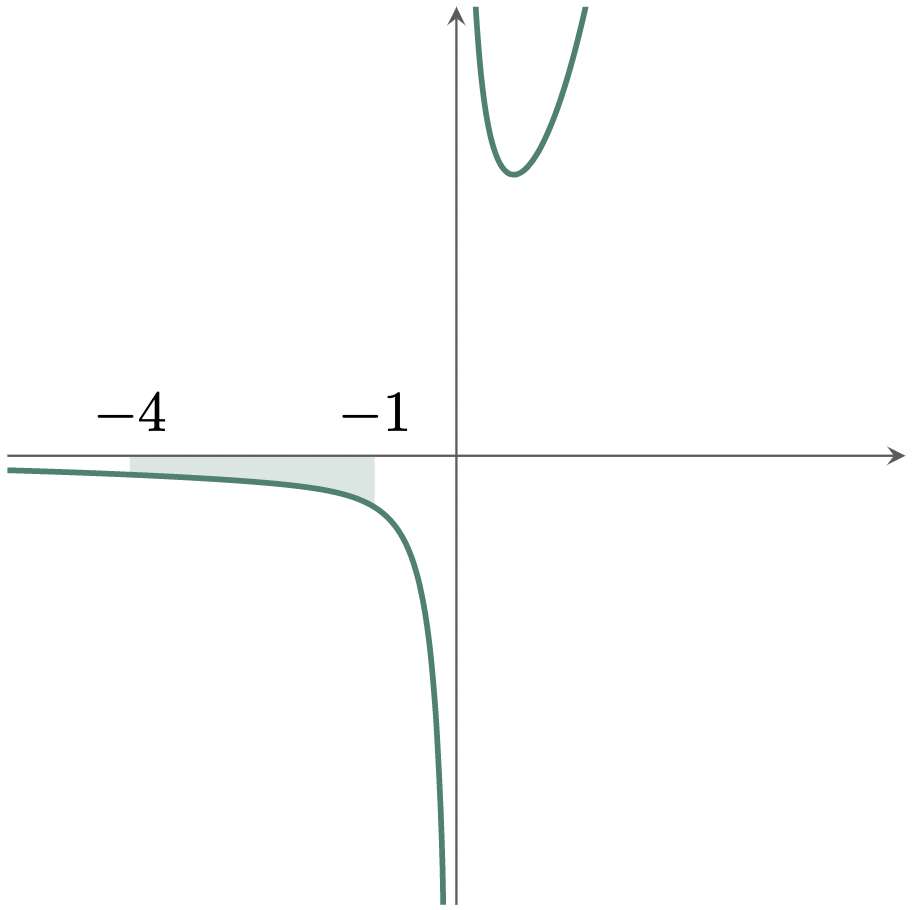

$\example{3}$ Evaluate the definite integral: $\int_{-4}^{-1} \br{e^x+\frac1x}\,dx$

$\solution$

\[\begin{align*} \int_{-4}^{-1} \br{e^x+\frac1x}\,dx &= \bbrk{e^x+\ln|x|}_{-4}^{-1} \\ &= \bbrk{e^{-1}+\ln|-1|} - \bbrk{e^{-4}+\ln|-4|} \\ &= \frac{1}{e}+\ln{1} - \frac{1}{e^4}-\ln{4} \end{align*}\]But from the properties of natural logarithms, $\ln{1}=0$. Thus,

\[\begin{align*} &= \frac{1}{e} +0- \frac{1}{e^4}-\ln{2^2} \\ &= \frac{1}{e}-\frac{1}{e^4}-2\ln{2} \tagans \end{align*}\]The decimal value of $\frac{1}{e}-\frac{1}{e^4}-2\ln{2}$ is approximately $-1.04$. By graphing the function, we can verify that it must be negative since the bounded area lies below the $x$-axis.

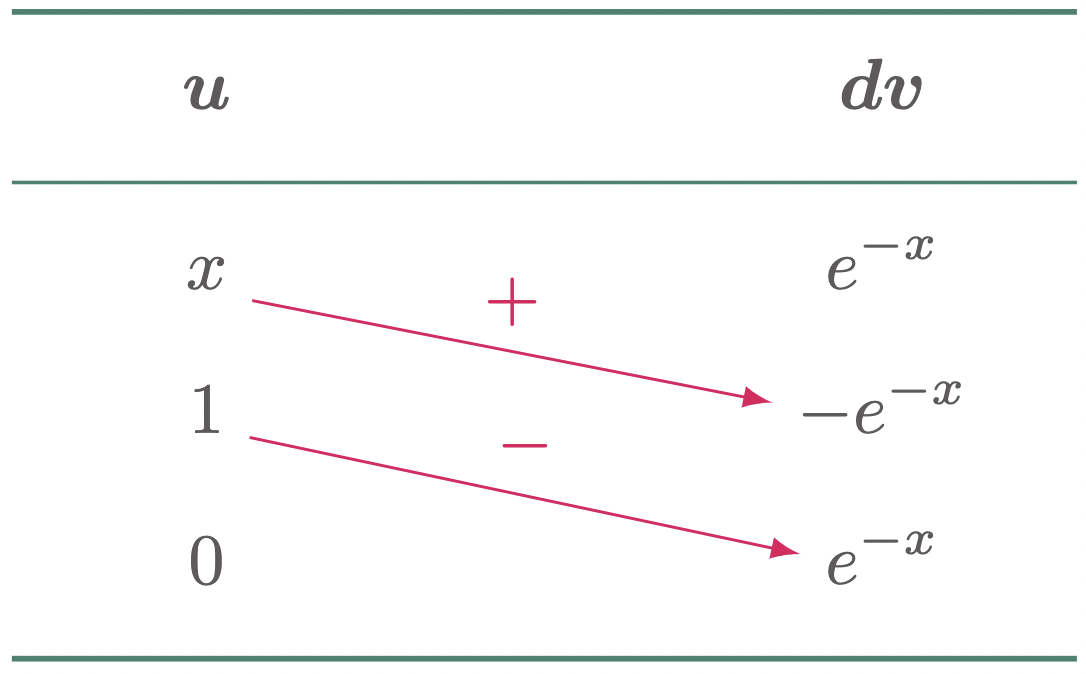

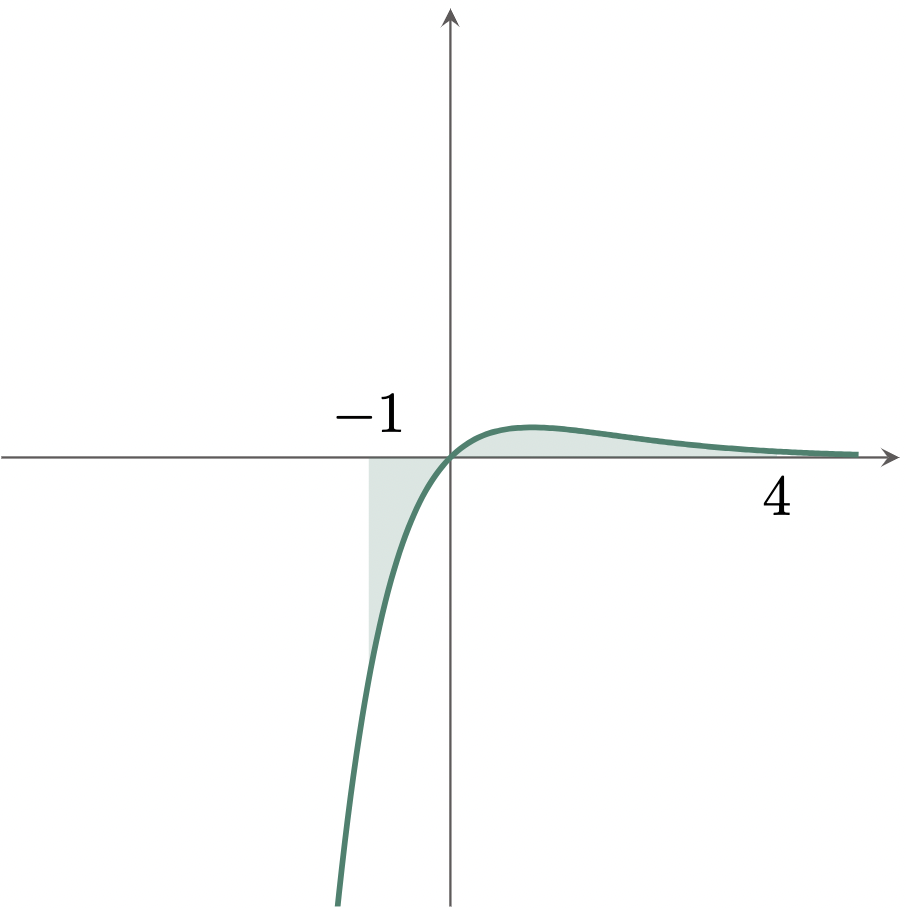

$\example{4}$ Evaluate the definite integral: $\int_{-1}^{4} xe^{-x}\,dx$

$\solution$

To solve the integral, use integration by parts. Since $x$ is an algebraic function and $e^{-x}$ is an exponential function function,

\(\begin{align*}

\text{Let:}\qquad u &= x & dv &= e^{-x}\,dx &&&&&&&

\end{align*}\)

Hence,

\[\begin{align*} \int_{-1}^{4} xe^{-x}\,dx &= \bbrk{-xe^{-x}-e^{-x}}_{-1}^4 \\ &= \brk{\frac{-x}{e^x}-\frac{1}{e^x}}_{-1}^4 \\ &= \brk{\frac{-x-1}{e^x}}_{-1}^4 \\ &= \brk{\frac{-4-1}{e^4}} - \brk{\frac{-(-1)-1}{e^{-1}}} \\ &= \brk{\frac{-5}{e^4}} - \brk{\frac{0}{e^{-1}}} \\ &= -\frac{5}{e^4} \tagans \end{align*}\]Graphing the function gives us,

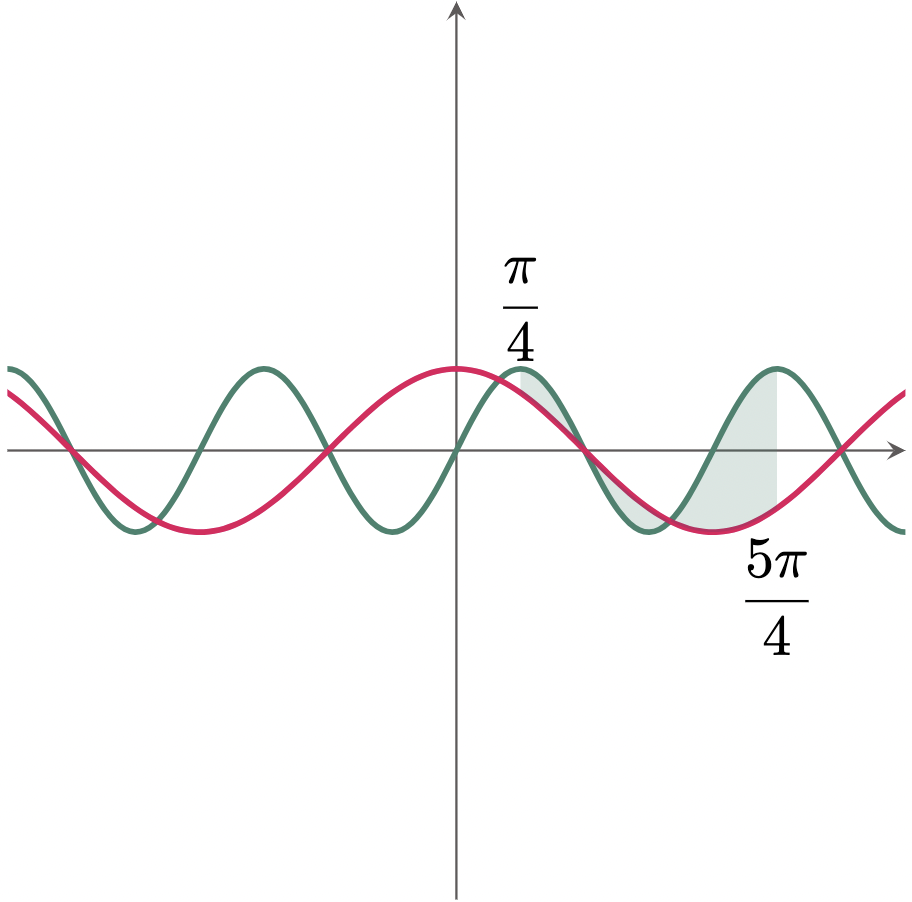

$\example{5}$ Evaluate the definite integral: $\int_{\pi/4}^{5\pi/4} \br{\sin{2x}-\cos{x}}\,dx$

$\solution$

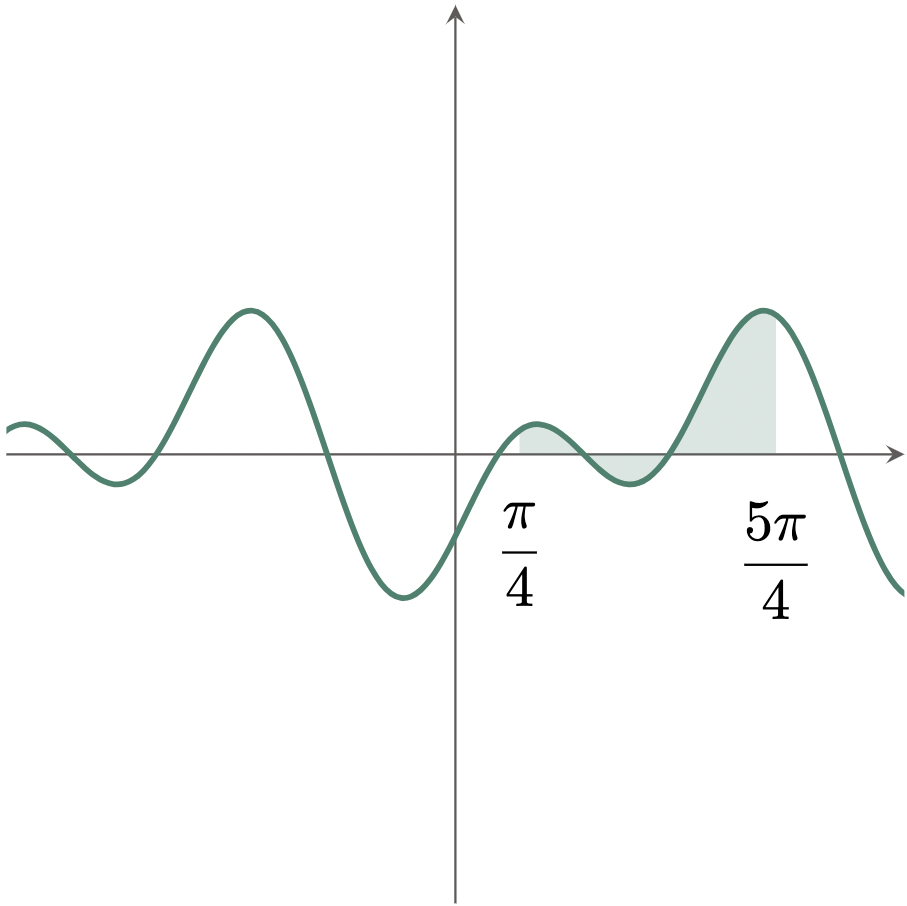

\[\begin{align*} \int_{\pi/4}^{5\pi/4} \br{\sin{2x}-\cos{x}}\,dx &= \brk{-\frac12\cos{2x}-\sin{x}}_{\pi/4}^{5\pi/4} \\ &= \brk{-\frac12\cos\br{2\cdot\frac{5\pi}{4}}-\sin{\frac{5\pi}{4}}} - \brk{-\frac12\cos\br{2\cdot\frac{\pi}{4}}-\sin{\frac{\pi}{4}}} \\ &= \brk{-\frac12\cos{\frac{5\pi}{2}}-\sin{\frac{5\pi}{4}}} - \brk{-\frac12\cos{\frac{\pi}{2}}-\sin{\frac{\pi}{4}}} \\ &= \brk{-\frac12\cdot(0)-\br{-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}}} - \brk{-\frac12\cdot(0)-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}} \\ &= \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} + \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2} \\ &= \frac{2\sqrt{2}}{2} \\ &= \sqrt{2} \tagans \end{align*}\]Graphing a difference of two functions can be done in several ways. One is to graph each function separately, then shading the area between the two curves at the given limits. This method is vital to note since the following lessons will have a similar approach as this.

Another method is to graph the integrand as is,

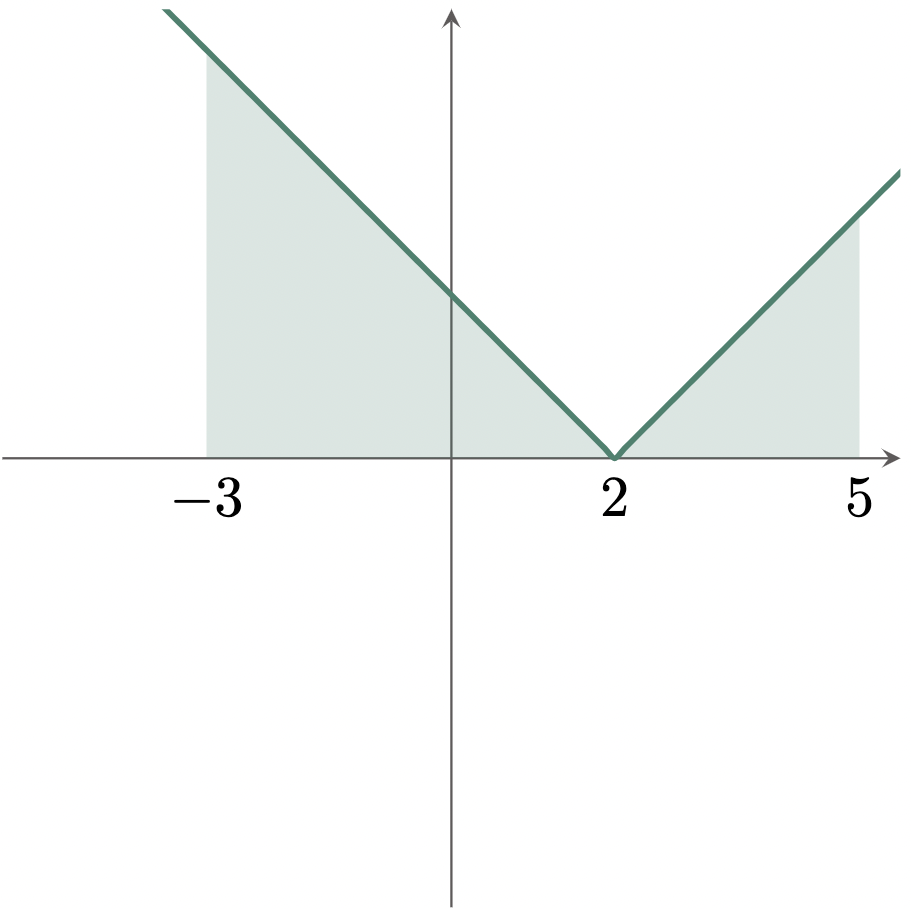

$\example{6}$ Evaluate the definite integral: $\int_{-3}^5 |x-2|\,dx $

$\solution$

In evaluating functions that contain an absolute value, we need to recall the ``piecewise function’’ to break down the absolute valued function into two parts.

\(|x-2|=

\begin{cases}

x-2, & \text{if $x \geq 0$} \\

-(x-2), & \text{if $x<0$}

\end{cases}\)

With this, we can graph the function to visualize how the limits will affect the function.

As we may have noticed, $x=2$ divides the function into two parts, thus using the property of “Addition of Interval,” we can rewrite the original integral as,

\[\begin{align*} \int_{-3}^5 |x-2|\,dx &= \int_{-3}^2 -(x-2)\,dx + \int_2^5 (x-2)\,dx \\ &= \int_{-3}^2 (-x+2)\,dx + \int_2^5 (x-2)\,dx \\ &= \brk{-\frac{x^2}{2}+2x}_{-3}^2 + \brk{\frac{x^2}{2}-2x}_2^5 \\ &= \brk{ \br{-\frac{(2)^2}{2}+2(2)} - \br{-\frac{(-3)^2}{2}+2(-3)} } \\ &\phantom{==}+ \brk{ \br{\frac{(5)^2}{2}-2(5)} - \br{\frac{(2)^2}{2}-2(2)} } \\ &= \brk{(-2+4)-\br{-\frac{9}{2}-6}} + \brk{\br{\frac{25}{2}-10}-(2-4)} \\ &= \brk{2+\frac{9}{2}+6} + \brk{\frac52+2} \\ &= \frac{25}{2} + \frac92 \\ &= 17 \tagans \end{align*}\]