We have already learned from the previous lesson that electrically charged particles at a distance either attract or repel one another.

However, have you ever wondered how does this occur?

These particles respond without even having a physical interaction with each other. They do not have strings or other mechanisms that would make them do so. This phenomenon in this modern era may not seem very impressive since we already have many wireless devices, but this was considered extraordinary in earlier times.

Physicists have come up with an explanation of this, which we now call the Electric Field.

Every electrically charged particle produces an electric field. It is a region of space around an electrically charged particle. When another particle is within that region, it would feel a force. The electric field of a charged particle exists at all points in space. However, its intensity decreases as it stretches until it can be approximated as zero.

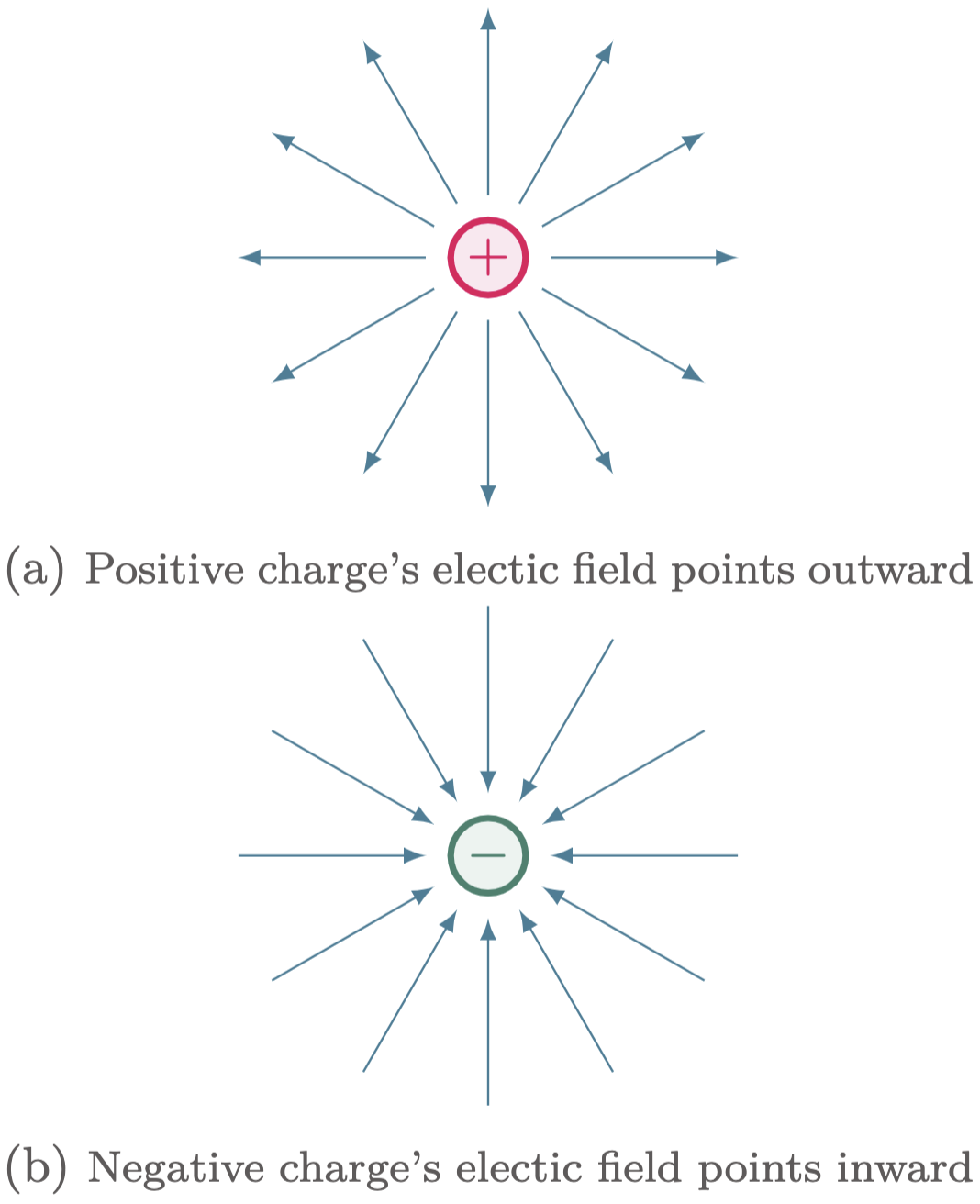

Electric fields are vector quantities and can be visualized as arrows going towards or away from the charges.

The lines radiate outward from a positive charge or inward toward a negative charge.

Figure 1: The direction of a charged particle’s electric field.

Calculating the strength of an electric field anywhere in space is rather complicated. Nevertheless, to simplify, we can determine its intensity at a particular position. All we need is a particle with a relatively small charge, which we shall refer to as the test charge, indicated by $q_0$. If a test charge is subjected to an electric force, this shows the presence of an electric field at that location.

The Electric Field $\vv{E}$ at the point where the test charge experiences a force $\vv{F}$ is equal to the force divided by the test charge.

$$\begin{align} \vv{E} = \frac{\vv{F}}{q_0} \label{eq:formula for electric field} \end{align}$$

One promising application of this is if we replace the test charge with another particle that carries a different charge, we could quickly evaluate the magnitude of the force that it would experience since the intensity of the electric field at that specific point would not change. Nevertheless, it will be best to try some examples using this formula.

$\example{1}$

A negative test charge $q_0 = 3.5\un{nC}$ experiences a repulsive force of $F=7.0\x 10^{-6}\un{N}$ from a charge $Q$.

(a) Determine the electric field at the point where the test charge is.

(b) If $q_0$ is to be replaced by particle that has a charge of $9.0\un{nC}$, how strong must the force be?

$\given$

\(\begin{align*}

q_0 &= 3.5\un{nC} = 3.5\x 10^{-9}\un{C} & \\

F &= 7.0\x 10^{-6}\un{N}

\end{align*}\)

After $q_0$ has been replaced with $q_1$,

\(\begin{align*}

q_1 &= 9.0\un{nC} = 9.0\x 10^{-9}\un{C}

\end{align*}\)

$\solution$

$\For{a}$

For the magnitude of the electric field at the point where $q_1$ is use $\eref{eq:formula for electric field}$,

$\For{b}$

Even if we replace the charge $q_0$, the electric field at the point where it was originally positioned would not be changed. Thus, we can rewrite $\eref{eq:formula for electric field}$ as,

$\example{2}$ A charge of $q = 20\un{\mu C}$ is in a vaccum. Using a test charge $q_0 = 0.5\un{\mu C}$, detemine the electric field at a point 0.25 m away where the test charge was placed.

$\given$

\(\begin{align*}

q &= 20\un{\mu C} = 20\x 10^{-6} \un{C} &\\

q_0 &= 0.5\un{\mu C} = 0.5\x 10^{-6} \un{C} \\

r &= 0.25\un{m}

\end{align*}\)

$\solution$

Using Coulomb’s Law, we can first find the magnitude of the force,

Then the magnitude of the electric field, use $\eref{eq:formula for electric field}$,

\[\begin{align*} E &= \frac{F}{q_0} \\ &= \frac{1.4384 \un{N}}{0.5\x 10^{-6} \un{C}} \\ &= 2.88 \x 10^{6} \un{N/C} \tagans \end{align*}\]As you may have noticed, we divided the result by the test charge $q_0$ after computing the force. With this in mind, we can derive a new equation for the Electric Field. Additionally, this example demonstrates that the electric field is independent of the test charge. As a result, the electric field of a point charge is,

$$\begin{align} E &= k\frac{|q|}{r^2} \end{align}$$

We can also use the equation to solve for the electric field in the preceding example.

\[\begin{align*} E &= k\frac{|q|}{r^2} \\ &= 8.99\x 10^{9} \un{N\frac{m^2}{C^2}}\frac{|20\x 10^{-6} \un{C}|}{(0.25\un{m})^2} \\ &= 2.88 \x 10^{6} \un{N/C} \tagans \end{align*}\]