From the previous sections, we have already learned kinematics to describe and solve motions in different dimensions. However, have you ever wondered why objects move in the first place? Or why does everything seems to come to a halt? In this section, we will try to understand the phenomenon that causes objects to move by introducing two new concepts: mass and force.

Force

In simple terms, a force can be described as a push or a pull. Alternatively, a force can also be defined as the interaction of two or more bodies. Forces are classified into two types: contact and noncontact. As the name implies, contact forces occur when objects come into contact with one another, such as when lifting a book or when two teams play tug-of-war. Noncontact forces, on the other hand, occur when no physical contact exists between the objects. The force between magnets are an example of noncontact forces; two magnets brought together at a relative distance experience either an attractive or repulsive force despite their separation. Another example of noncontact forces is our weight, the gravitational force that the earth exerts on our bodies.

Mass

If you’re wondering about mass, yes, there is a difference between mass and weight. Mass is a property of matter and a measurement of inertia. We can also think of it as the resistance to acceleration when force is applied; however, we will discuss this concept in greater detail in the following section. In the International System of Units (SI), the mass has a unit of kilograms (kg).

Oftentimes, mass is confused with weight. Mass simply measures the amount of matter confined within an object. On the other hand, weight relies on the pull of the earth or any planet you may be located on. For instance, a 5 kg ball here on earth will still be 5 kg on the moon. Its weight, however, will be less on the moon. Mass remains constant regardless of its location.

Super Position of Forces

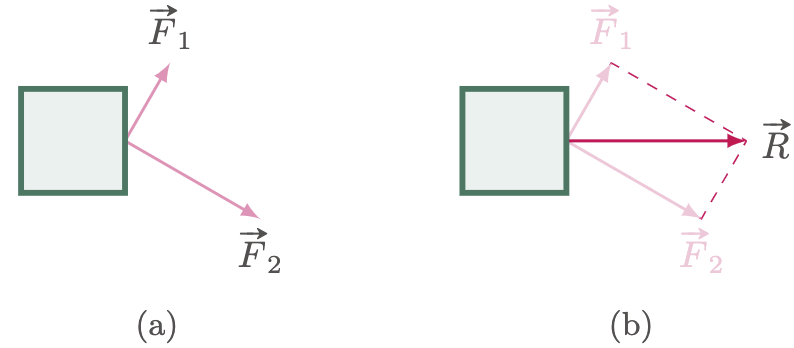

A force is a vector quantity; thus, noting the force’s direction is crucial in understanding the interactions of the different forces that act on an object. With this in mind, we may soon come across the term “net force,” which refers to the vector sum of all the forces acting on an object $\textstyle{\sum \vv{F}}$. We must consider all the forces that act on the object, as each contributes to the net force. For instance, in $\fref{1}$, a block is pulled by two workers. The two individual forces $\vv{F_1}$ and $\vv{F_2}$ can be expressed by a single force through vector addition $\vv{R}$.

Figure 1: Vector addition can be used to express multiple forces as a single force.

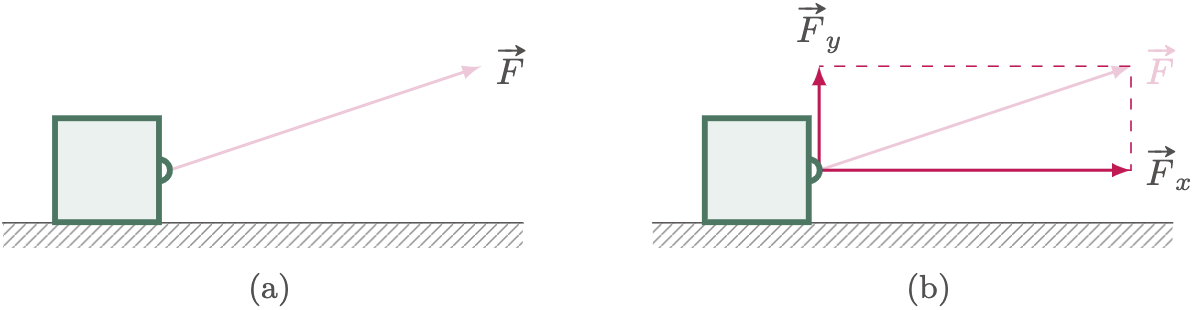

Additionally, we can use this notion to break down a force acting at an angle $\vv{F}$ on an object into several components. For instance, a string is used to draw a block at an angle to the horizontal, and this force can be expressed as two forces $\vv{F_x}$ and $\vv{F_y}$.

Figure 2: In some cases, decomposing a force into several components can significantly reduce the complexity of the problem.

This is especially advantageous when several forces are pointed in different directions; changing to parallel forces relative to different forces simplifies the solution significantly since parallel forces are easier to calculate since we no longer need to worry about their angles.

When dealing with two-dimensional forces, it is best to break down all the forces into two perpendicular components; usually, we will use the horizontal and vertical axis, except in cases where having an angle will make the problem much easier to solve.