In the seventeenth century, Sir Isaac Newton established the foundations of what we now know as Classical Mechanics, often referred to as Newtonian Mechanics. However, we are more concerned with its underlying principles, which are Newton’s Laws of Motion. Newton established three fundamental laws, and in this section, we will try to grasp and build up our understanding of these laws.

First Law of Motion

“An object at rest will remain at rest, and an object in motion will retain its motion at a constant velocity, unless acted upon by an external force.”

The first sentence is relatively self-explanatory: “an object at rest will remain at rest”; a car parked on the stable ground will almost certainly not move unless someone intends for it to do so or until some force acts upon it. The second statement may appear counterintuitive since we are accustomed to the assumption that everything eventually comes to a halt, just as the ball that’s thrown upwards will soon fall and will eventually stop moving. However, assuming that we take all the external forces away, such as gravity and the air resistance, the ball is supposed to continue traveling at a constant pace throughout perpetuity. With this in mind, force does not cause a moving object to continue moving; rather, it enables it to stop moving.

In both cases, a body at rest or a body moving with a constant velocity in a straight line are said to be in equilibrium and experience zero net force.

$$\begin{align} \sum F = 0 \quad\text{(body in equilibrium)} \end{align}$$

The First Law of Motion is sometimes called the Law of Inertia. To illustrate what inertia is, consider the following scenario. Pushing a motorcycle from rest requires less force than pushing a car in the same condition. By applying the same force to both vehicles, we can deduce that the motorcycle will achieve a more significant change in velocity than the car. Similarly, if both vehicles are moving at the same rate, stopping the car will take greater force than the motorcycle. In this case, we can say that the car has larger inertia than the motorcycle. Inertia is simply the resistance of the object to change its velocity.

If you’re familiar with the meme in $\fref{1}$, this is a perfect example of the Law of Inertia. While the vehicle may be equipped with breaks, the boulder it is transporting has none. As a result of its large mass and inertia, the boulder’s natural tendency is to continue moving. We can also observe this behavior while driving a car; if the brakes are applied suddenly, our body’s natural impulse is to continue forward. However, compared to a boulder, the effect on us is not that profound since we have less inertia than the boulder.

Figure 1: The boulder has no breaks

To easily remember the first law, it is simply the tendency of the object to maintain what it is already doing stubbornly.

Second Law of Motion

According to the first law, motions with zero net force exist when a body is at rest or moving at a constant velocity (no acceleration). However, in the following law, we will attempt to comprehend motions that experience a net force.

For instance, a boy pushes a wagon from rest. The wagon with a mass $m$ would most probably accelerate. Furthermore, if the wagon is loaded and the mass is increased while maintaining the same force, the acceleration will most likely be smaller than it was previously.

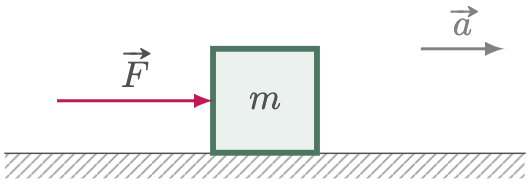

Figure 2: The direction of the net force is the same as the acceleration.

This concept enables us to describe the relationship between the three parameters. Acceleration is directly proportional to the net force, and its magnitude is inversely proportional to the mass. Note that the direction of the force is the same as the acceleration.

$$\begin{align} \vv{a} = \frac{\sum\vv{F}}{m} \\ \qquad\text{or}\qquad \nonumber \\ \sum\vv{F} = m\vv{a} \end{align}$$

SI Unit of Force: $\mathrm{Newton \,(N)}=\mathrm{kg\cdot\frac{m}{s^2}}$

One Newton is the amount of net force required to accelerate a mass of one kilogram to one meter per second squared.

The net force in Newton’s Second Law relates to external forces, as everything requires an external force to move. If it were possible for a body to affect its own motion, we don’t need a floor to walk; we can simply levitate and walk on air.

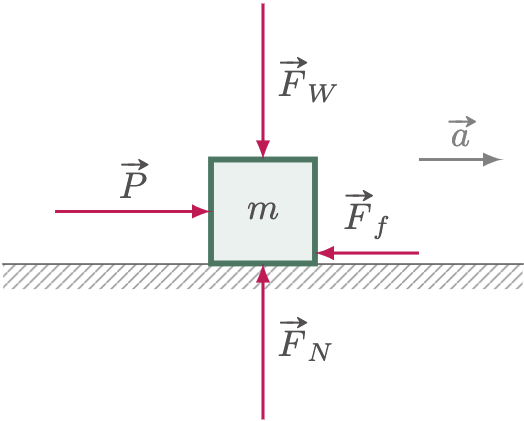

To understand how external forces affect an object, let’s have another example. For instance, you are pushing a crate on flat ground. The crate experience several forces: An applied force that you apply to the crate, a frictional force that resists the crate’s sliding motion, its weight, and the ground’s normal force. In this case, the forces acting on the vertical axis cancel out. Otherwise, the crate would float or sink, depending on which force is greater. As a result, we will concentrate on two forces parallel to the horizontal axis: the applied force $\vv{P}$ and the frictional force $\vec{F_f}$, as the motion will most certainly occur along this axis. We can already determine the direction of the crate solely by intuition; it will be in the same direction as the applied force $\vv{P}$. As a result, it is preferable to label the direction in which $\vv{P}$ points as positive. Hence, the net force $\textstyle{\sum \vv{F}}$ is equivalent to the vector sum of the horizontal forces $\vv{P}+(-\vec{F_f})$.

Figure 3

Third Law of Motion

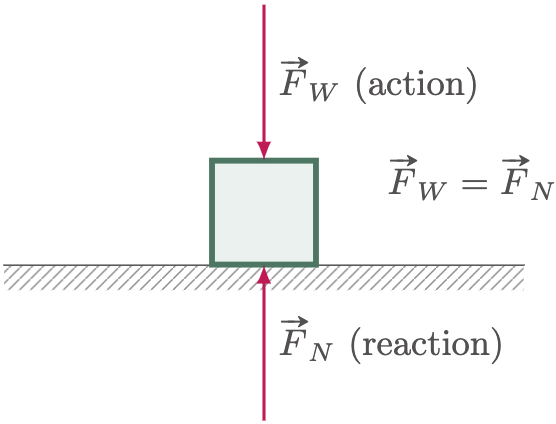

The third law of motion is often called the “Law of Action-Reaction”, since some may quote it as “For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.” Where whenever an object exerts a force to another object, the second object exerts a force that has the same magnitude as the first object but opposite in direction.

For you to stand still on the floor, an opposite force reacted by the floor to your feet is what enables you to stand still. If ever the floor does not give the same amount of force in an upward direction, you would inevitably fall since your body always experience an external force, your weight, which points in a downward direction; or in a different perspective, to the center of the earth.

Figure 4

This law also explains why punching a concrete wall is much more painful when you punch harder. The amount of force you exert while punching the wall will be the same as the force of the wall towards your fist. If you come to think of it, if you punch something, it will punch you back with the the same amount of force.

Mathematically, we can express the third law of motion as:

$$\begin{align} \vec{F_{12}} = -\vec{F_{21}} \end{align}$$

Where $\vec{F_{12}}$ is the force exerted by object 1 to object 2 (action), and $\vec{F_{21}}$ is the force exerted by object 2 to object 1 (reaction). The negative symbol denotes that the force of the second object is pointing opposite the force of the first object.